|

|

Development

and Employment of Soviet Armor Tactics Prior to and During the Great Patriotic

War

Page 2

As the Russian resistance to the Germans crumbled, so did the resistance

to the central role of the army being switched from infantry to armor.

The high command realized that their current emphasis on infantry

could not, and would not, stop the German advance. With this knowledge,

they began to modify the composition and tactics of the army accordingly.

New tank brigades and corps were formed, using the superb T34, with

command positions going to tank commanders who had survived battle

against German tanks. Initially, the tank forces were used only defensively,

and not offensively, due to the fact that the Red Army was in no condition

to mount, nor was Russia economically or industrially prepared to

supply, a counter-offensive.

The first order of business for the Red Army had to be stopping

the Germans, and the tactics of the reinvented Soviet army clearly

reflect this. The Soviets went to great lengths in their effort to

build and man a modern mechanized army. The Red Army enlisted thousands

of soldiers to man the new tanks, and in a very short training period,

"emphasized driver’s skills, basic gunnery, limited but controlled

movements and defensive tactics."9 The training given in

the early stages of the war dealt only with the defensive, with scant

attention given even to counter-attack. This bare-bones defensive

training reflected the dire situation that the Soviet Union faced.

Giving only the minimum essentials for combat, and nothing else, Soviet

armor training was an effort to man tanks, not to fully prepare men

for war. By following the doctrine of quantity over quality, the Red

Army desperately gambled to quell the German onslaught.

The success and survival of the Soviet Union depended entirely upon

the integration and effective use of armor by the Red Army. The Soviets

hoped to accomplish this with the help of the newly formed tank brigades,

and the new defensive tactics. The extremely conservative defensive-minded

doctrine had little emphasis or tolerance for counter attack, and

no place whatsoever for the offensive. Tactics of sheer survival,

the Red Army embraced the following principles:

1. "As a rule, tanks are used in the defense"10

2. "Destroy attacking enemy by fire from stationary positions"11

3. "Selecting terrain favorable for committing tanks and improvement

of field fortifications."12

Soviet high command implicitly stated that armor was a defensive

weapon, to be used only in a defensive manner unless the situation

prevented such usage. Going beyond that, they dictated that tanks

should be used primarily while stationary, preferably sheltered

in fixed fortifications. Though not the most effective manner of

employing armor, the Red Army was in such a position that offensive,

even counter-offensive, operations were infeasible. The severe shortage

of materiel and the advancing German army dictated a policy of pure

defense. By following the course of defense, the Soviets traveled

the only viable avenue open to them. Though the only option, it

was not an inferior or incorrect option; it was actually the best

alternative available for Russia.

The future for the Soviets, however, still looked grim. The German

Army was so close to Moscow that the spires of the Kremlin were in

sight. Moscow, the base of political, economic, and military command,

as well as the center of the Russian rail network in Europe, had to

be held at all costs. The Red Army, however, was in a state of disarray

and general defeat. Much of the army still "did not know how to maneuver

defensively,"13 and fought the Nazis in a manner that barely

slowed the machinelike German advance. However, the influx of men,

machines, and strategy began to have a visible effect in the last

months of 1941.

In late November, the Germans threatened the Russian capital from

both the north and the south. By this time, however, the Soviets had

amassed a semblance of a tank force, as well as many battle-hardened

soldiers to man them. The Russian tank force was still considerably

inferior to that of the Germans, but the Panzer army under General

Guderian was nonetheless unable to defeat the Russian 4th

Tank Brigade, with the Russians forcing a stalemate by early December.

The thrust from the north fared no better, being stalemated by December

as well. Facing defeat at the hands of the Russians for the first

time, Guderian reported that the "‘new tactical handling of the Russian

tanks was very worrying.’"14 Indeed, the successful defense

of Moscow foreshadowed that the shift to an emphasis on armor could

shift the tide of the war as well. Once the safety of the capital

had been secured, the Red Army made the decision to counter-attack

On November 29, 1941, the Russian army, through the use of massed

armor formations, liberated Rostov, the "Gateway to the Caucasus".

Rostov had been captured by the Germans six days earlier, with heavy

casualties on both sides. The counter-attack against German forces

in Rostov, though very costly, was highly significant. The very fact

that a counter-attack, though only a local counter-attack, was possible,

spoke well for the Soviets, since just days earlier they had been

limited to desperate defense. The counter-attack was especially meaningful

for the soldiers, since they had been taught that the offensive was

the "‘fundamental aspect of combat for the Red Army.’"15

In the waning months of 1941 and the early months of 1942, the tide

began to turn along most of the front as it had in Rostov. The Soviets,

aided by rapidly increasing industrial production, as well as the

harshest winter in over a century, returned to the "fundamental aspect"

of combat—the offensive.

In December of 1941, after Moscow had been spared and Rostov liberated,

the Red Army launched its first general counter-offensive of the war.

In this counter-offensive, the new emphasis on the role of armor was

highly visible. In contrast to the early months of the war, when tanks

were allocated to infantry battalions, the Moscow counter-offensive

featured eighteen autonomous tank brigades and nineteen independent

tank battalions, in addition to the nearly one million infantrymen.

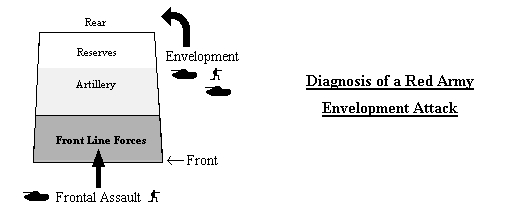

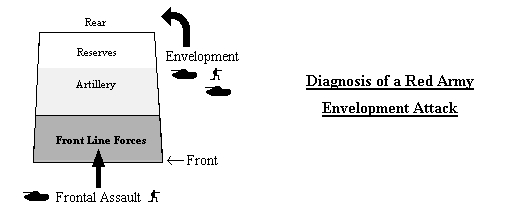

The Red Army, drawing tactics from the extremely successful German

army, shifted away from the policy of pure defense and adopted a counter–attacking

policy of envelopment. Much emphasis was still placed on defense,

for the Russians were still in an extremely tight situation. However,

for the first time, the Red Army embraced offensive, albeit counter-offensive,

actions against the Germans. Their policy of envelopment involved

a frontal assault on the opposing forces, while a larger force attempted

to swing around the enemy.

After a German attack had been slowed or halted, a frontal counter-attack

would be launched. This frontal attack would draw artillery support

and reserve forces to the front, opening the way for a second, larger

wing of Russian forces to envelop the weakened rear of the Germans.

After the larger force enveloped the enemy from his rear, the two

wings would work towards each other, in effect smashing enemy forces

between them. This method, while greatly successful for the Germans,

was less successful for the Soviets, for a variety of reasons.

The Red armor crews, because of their rudimentary training, were

not accustomed to offensive maneuvers and were in fact rather disconcerted

with offensive action. In addition, though industrial production was

on the upswing in the fall of 1941, output was still much too low

to adequately support the counter-offensive operations. The low "tank

production made it impossible to provide the requisite number of tanks

necessary to equip [the] brigades"16of the counter-offensive.

Russian tank battalions still contained far fewer tanks than their

German counterparts. Though the forces looked mighty on paper, they

seemed hollow and weak in comparison to the powerful Panzer battalion,

and this disparity showed in battle.

Because of this hollowness, the Red armor battalions, though beginning

to become capable fighters, were unable to envelop German forces and

press attacks to the point of complete operational success. The degree

of success, however, constantly improved with time. Industrial output,

at the end on 1941, and especially during 1942, began to increase.

The expansion was to such a great degree that the Soviets were finally

able to fill out the ranks of armor battalions with badly needed tanks.

The Red Army, with battalions no longer undermanned, ground the Nazi

advance to a halt, and even began to repulse the Germans.

After the German advance had been stopped, and the Wermacht assumed

a general defensive stance, the Red Army’s policy of enveloping counter-attacks

was no longer applicable to the situation. A viable offensive policy

was needed to continue the struggle against the fascist invaders.

Accordingly, the high command began searching for a solid offensive

strategy. The more they looked, the more they came back to the "deep

operations" plan of the 1920s and 1930s. "As the war progressed, the

ideas of Soviet military strategists and tacticians of the 1920s and

1930s came into wide use."17 The idea of deep operations,

slightly modified, became the tactic of choice for the Soviets through

the war’s end.

Deep operations is the idea of creating a hole in the front line,

and exploiting it deep into enemy territory. The 1920s and 1930s version

of the plan emphasized infantry over armor, but the lessons of 1941

led the Soviets to give the dominant role to tanks. Clearly, infantry

plays a large role in any land war, but placing infantry with armor,

instead of armor with infantry, greatly increases the versatility

and power of military forces. The change in emphasis from infantry

to armor, however, was not the only change that the World War II era

strategists made. Instead of creating only one hole in the enemy line,

the Soviets of the 1940s proposed that two breakthroughs be created.

The two breakthroughs in the front line were to be created through

direct frontal attacks. Through these holes, great masses of armor

and mechanized infantry would be poured. The creation of two holes

would split enemy forces into two, or even three sections, thereby

greatly reducing the operational might of the opposing forces.

The revised deep operations plan was essentially a combination of

the 1930s deep operations plan and the envelopment doctrine. By splitting

and surrounding the enemy, the Red Army was in effect enveloping the

opposition. The major difference between the new deep operations plan

and the envelopment plan was the manner in which the envelopment was

achieved. The envelopment doctrine called for the creation of the

envelopment through the use of diversionary attack and maneuver, whereas

the modified deep operations plan dictated that brute force was the

method to achieve envelopment.

As the war progressed, and Soviet industry produced more and more

armor (by war’s end, the Soviet Union had produced over 40,000 T34s)18,

this method of warfare became increasingly effective. Any army, no

matter how experienced or zealous, will break in the face of repeated

human wave attacks. The German army, increasingly demoralized and

under-supplied, simply could not fend off the massive frontal attacks

presented through the revised deep operations plan. The deep operations

plan succeeded not because of tactical wizardry, but because it utilized

the tremendous manpower advantage of the Soviet Union. Full frontal

assaults, effective when pressed until the enemy breaks, consume mass

quantities of men and machines before a breakthrough is created. This

grisly facet of the plan, however, did not concern the planners. While

the Germans won their battles through speed, maneuver, and intelligence,

the Red Army resorted to brute force because it was simple, it worked,

and they could absorb the horrific losses.

For the remainder of the war, Soviet armor tactics remained relatively

unchanged. Slight modifications to the new deep operations plan were

made locally for variations in terrain, weather, and enemy opposition.

The basic tenets of the plan, however, remained the same. Victory

was achieved by overwhelming defenders with masses of men and machines,

and mercilessly crushing all resistance. Through 1942, 1943, 1944,

and 1945, the Red Army refused to adopt more efficient tactics, instead

opting for the simplest option available. This may have been due to

the extreme political nature of the Soviet military, which had little

tolerance for initiative, and stressed compliance and ultimate victory

over efficiency. Fortunately, as the army became more proficient,

and the Germans became weak and demoralized, the brutish tactics of

the Soviets did become more efficient, as well as less costly. The

constantly shifting tactical policy of the Red Army, both prior to

and during World War II, clearly affected the performance of the Soviets

against the Nazi invaders. The incorrect pre-war assumptions of the

high command led to the severe weakening of the Red Army mechanized

armor branch. This weakening was so great that it nearly destroyed

the role of armor in the Soviet army. In an era of warfare so dependent

upon mobility and firepower, the tank, the perfect mixture of the

two, was clearly the decisive weapon. Therefore, the decisions that

led to the weakening of the Soviet armor branch greatly weakened the

whole of the red Army, almost to the point of debilitation.

This near total incapacitation of the Soviet military became readily

apparent in the opening stages of the war between Russia and Germany.

In June of 1941, the Germans strolled across Russia, crushing Soviet

opposition seemingly at whim. The German army, with the strongest

tank force in the world, was so vastly superior to the depleted ranks

of the Red Army that German victory seemed inevitable. However, the

tide of the war was turned when the Soviets began shifting their military

emphasis from infantry to armor.

By at first emphasizing defensive basics, and slowing the German

advance, the Red Army gave itself time to reconstruct a respectable

armored force. The T34, the greatest tank of the World War II era,

gave the Soviets an edge once their tank forces began to materialize.

Once the forces were created, and the Russians had the resources to

launch counter-offensives, which they promptly did. With the counter-attacks,

the Red Army ground the German advance to a halt, and for the first

time on the eastern front, put Germany on the defensive. This further

aided Russia by allowing the Soviets to build, man, and train one

of the largest armored forces in the world. This awesome armored force,

aided by the second largest infantry army on the planet, and an increasingly

competent air force, simply could not fail.

Though the Germans made some small gains after their initial advance

halted, they could not match or defend against the sheer size of the

now technologically equal Red Army. Even before the battle of Kursk,

the largest battle on any front in World War II, in which the Germans

made fairly substantial gains, or their last offensive in 1944, the

fate of Nazi Germany was sealed. Once the drive to the east had been

halted, and the Red Army began throwing millions of men and machines

at the Germans, it was merely a matter of time.

Had the Soviets chosen more effective tactics, instead

those of brute force, the war may have ended sooner, which would have

saved millions of dollars and lives. However, the Red Army realized

that it could afford the costs of such tactics, and it went ahead with

them. Though hardly brilliant, the human wave tactics employed by the

Soviets against Germany in World War II had the desired effects. The

quality of the Russian armored forces, namely the T34 tank, combined

with the vastness of the Red Army, precluded any possibility of a German

victory. As German Panzer general F.W. von Mellenthin put it, "the Russian

form of fighting—particularly in the attack—is characterized by the

employment of masses of men and material, often thrown in unintelligently

and without variations, but . . . [it is] effective."19

Endnotes

1 Scott, Harriet and William eds., The

Soviet Art of War: Doctrine, Strategy,

and Tactics, Boulder Colorado: Westview Press, 1982, 19

2 Armstrong, Richard N. ed. Welsh, Joseph G. trans., Red

Armor Combat Orders: Combat Regulations

for Tank and Mechanized Forces 1944,

London, England: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., 1991, x

3 Ibid., p. x

4 Ibid., p. xi

5 Scott, Harriet and William eds., The Soviet

Art of War, 288

6 Ibid., p. 21

7 Mellenthin, Major General F.W. von, Panzer Battles:

A Study of the Employment of

Armor in the Second World War,

London, England: Cassell & Co., 1955, 159

8 Armstrong, Richard N. ed. Welsh, Joseph G. trans., Red

Armor Combat Orders, xii

9 Ibid., p. xii

10 Ibid., p. 116

11 Ibid., p. 116

12 Ibid., p. 117

13 Paret, Peter ed., Makers of Modern

Strategy: From Machiavelli to the

Nuclear Age Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University

Press, 1986, 672

14 Armstrong, Richard N. ed. Welsh, Joseph G. trans., Red

Armor Combat Orders, xiii

15 Paret, Peter ed., Makers of Modern

Strategy Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986,

672

16 Armstrong, Richard N. ed. Welsh, Joseph G. trans., Red

Armor Combat Orders, xiii

17 Paret, Peter ed., Makers of Modern

Strategy Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986,

672

18 Goralski, Robert, World War II Almanac:

1931-1945: A Political and Military

Record New York, New York: Bonanza Books, 1981, 438

19 Mellenthin, Major General F.W. von, Panzer Battles

London, England: Cassell & Co., 1955, 296

Bibliography

Armstrong, Richard N. ed. Welsh, Joseph G. trans., Red

Armor Combat Orders: Combat Regulations

for Tank and Mechanized Forces 1944

London, England: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., 1991

•Translated original orders and regulations for Soviet tank and

mechanized forces. Excellent for viewing transforming Red Army tactics

and strategy. Also useful for verifying other information, since it

is genuine Red Army material. My primary source.

Carver, Field Marshal Lord, The Apostles of

Mobility: The Theory and Practice

of Armoured Warfare New York, New York: Homes

and Meier Publishers, 1979

•Traces strategy and tactics of tank warfare from World War I through

the early seventies. Used mainly in my research of pre-World War II

armor.

Goralski, Robert, World War II Almanac:

1931-1945: A Political and Military

Record New York, New York: Bonanza Books, 1981

•Background source, used for logistical information, dates, etc.

Best World War II almanac/timeline I have seen.

Macksey, Kenneth, Tank Warfare: A History

of Tanks in Battle New York, New York:

Stein and Day Publishers, 1972

•Mainly a background source, used for studies of German World War

II panzer tactics, and to some extent the Soviet response to them.

Some useful specific and unique information.

Mellenthin, Major General F.W. von, Panzer Battles:

A Study of the Employment of

Armor in the Second World War

London, England: Cassell & Co., 1955

•Panzer General’s account and interpretation of World War II tank

warfare. Primary source for German tank strategy against Russia. Overall

good, but in some places biased and subjective (he seems to be a fairly

devout Nazi). ex. "The Russians were strong, but we had Adolf Hitler!"

(or something similar)

Murray, Williamson, The Making of Strategy

Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1994

•Outlines the creation of overall Soviet strategy from World War

I through World War II, with some attention paid to tanks. Only a

few chapters relevant to time period of topic.

Paret, Peter ed., Makers of Modern Strategy:

From Machiavelli to the Nuclear

Age Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1986

•Discusses role of Stalin in Red Army strategy, as well as development

of Soviet strategy World War I through World War II. Again, only a

few chapters relevant to time period of topic.

Scott, Harriet and William eds., The Soviet Art

of War: Doctrine, Strategy, and

Tactics Boulder Colorado: Westview Press, 1982

•My second chief source, an overview of Soviet strategy and tactics

from World War I to the late seventies. Not a great portion of material

deals with World War II, but relevant material is excellent.

| |

|

Copyright

© 1994-2005 Stephen Payne

|

|